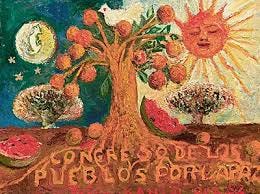

Frida Kahlo (Mexico; 1907-1954) “Congress of Peoples for Peace.”

The Sea of Faith/Was once, too, at the full.../But now I only hear/Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar. Matthew Arnold [England, 1822-1888] "Dover Beach," 1867.

Each succeeding generation has navigated by its own Zionist compass, whether it is the story of pioneers draining the swamps and “making the desert bloom”; or a haven for Holocaust survivors; or a tiny nation surrounded by Arab enemies and courageously defending itself. The bravery narrative had certain symbols – the Six Day War and the recapturing of the Old City of Jerusalem; hanging on by a thread on Yom Kippur, 1973; rescuing the hostages at Entebbe; Natan Sharansky defying the Soviet Union and making aliya after years spent in a Russian jail cell on a trumped-up charge.

But the icons of one generation may be lost on the next; the news cycle does not wait for anyone. Multiple generations of Jews have now grown up with different code words: occupation and injustice; and more recently apartheid, ethnic cleansing, colonialism, genocide. These words have impacted all Jews, but for some, they are a cue to part ways with the larger pro-Zionist Jewish community and stake out an anti-Zionist stance. The reasons for this phenomenon are diverse, but its roots partially lie in an argument over what constitutes the core of Judaism.

The mainstream community often brands such Jews as self-hating, but the story is more complicated than that, and can be traced, ironically, to their belief in certain Jewish values as paramount. For instance, here is Zia Laboff, an Oregon member of Jewish Voices for Peace, which is an explicitly anti-Zionist group: “It’s very difficult to seek spaces of Jewish spirituality that aren’t tied up in some way with Zionist funding or Zionist ideals…[and] which I think are antithetical to Jewish values.”

Her co-member Nate Cohen, describes it this way: “When I see a community for whom the spirit [of resisting oppression] is so deeply entwined in our collective identities, and then committing atrocities and war crimes against other people, I just feel like it is so wildly disconnected from what I understand Judaism to be. The biggest entity in the world, that claims to speak for our collective identity, is doing things that go so inherently against my understanding of what that identity is.”

Members of the Jewish Voice for Peace and the If Not Now movement, two Jewish activist groups, stage a rally on Oct. 18 in Washington, D.C., to call for a cease-fire in the Israel–Hamas war.

You will notice in the above picture that the protesters openly identify as Jews. Where did this particular understanding regarding “true” Jewish identity begin, and where was it nourished? For older Jewish adults who participate in such rallies, the impulse may have been influenced by the peace marches of the 1960’s. In the case of younger Jews, however, it stems partly from the kind of Jewish education or messaging they received in the last 40 years, especially in non-Orthodox contexts. The latest Pew Study, released in 2021, reports that “most Jewish adults say that remembering the Holocaust, leading a moral and ethical life, working for justice and equality in society, and being intellectually curious are “essential” to what it means to them to be Jewish. Far fewer say that observing Jewish law is an essential part of their Jewish identity.”

In other words, being Jewish is largely about being a good person and remembering our collective trauma. But can’t you be a good person and not be religious, or even Jewish? And the answer is, of course you can, so if the sum of Jewish wisdom is “to be a mensch,” then Judaism’s utility is reduced to being the sweet icing on top of an already baked cake. It’s a bonus, but not essential to the project of goodness.

But didn’t Jewish schools and shuls and summer camps try to imprint a love of Zion within their charges? Yes they did, and for many young Jews, the message was received with appreciation or at least not a sense of alienation. Yet at the same time, these institutions were also focused on a different lesson, one they never dreamed could run counter to enthusiasm for the Jewish State.

The late sociologist of religion Peter Berger describes what he calls a kind of surrender on the part of many contemporary Christian theologians, and I think it well applies to the Jewish world as well, where certain ideas are substituted for traditional religion: “the alleged ethics of Jesus, or some sort of existentialist experience, or mental health with a spiritual component, or some particular political agenda.” Prof. Berger sees these substitutions as “a kind of suicide... as people discover they can be ethical without Jesus, existentially authentic and mentally healthy without religion, and political without the church.”

It is likely that a swathe of the current wave of Jewish anti-Zionists were raised precisely on the mother’s milk of a “new Judaism” in which their teachers, sensing that what one might call the “old words”—halacha; obligation; sin; reward; punishment--would in fact be rejected, pivoted exclusively to new kind of language—religion as self-growth; or a search for authenticity; or being a good person.

“God” – out; “tikkun olam” – in. “Shul attendance” – out; “spirituality” – in.

Thus, a certain segment of Jews latched on to the identification of the Judaism they could relate to or connect with exclusively within the auspices of goodness-peace-love your neighbour-do not oppress the stranger-universal brother/sisterhood.

I am not mocking this impulse; all of these ideals can be inspiring in and of themselves. But when applied to a nationalistic project like Zionism--one that, tragically, can only be maintained by some exercise of force and the spilling of blood—a clash of priorities is inevitable. At the end of Megillat Esther, there is a torrent of violence, as the Jews “assembled to protect themselves and get relief from their enemies. They killed seventy-five thousand of them…” [Esther, Ch. 9]. Commenting on these battles, the Israeli thinker Yoram Hazony writes: “Being good is today very closely allied with the revulsion we have learned towards the killing of children, the aged, and other non-combatants in war...Purity requires that man renounce power; but morality requires that man have power in order to pursue right...Without power, there is no police force capable of defending the innocent, no court capable of doing justice, no army capable of wresting peace from the aggressor.”

Is it possible to reconcile power with goodness and purity? Is there a way out of this dilemma? I will explore the problem further in an upcoming post, soon.

Feel free to share this post and, please, recommend my Substack to others. I’d be interested in all of your views about the above piece. Please write into the comments section and let me know how you think.

No matter where you live, I am available to come and address your community as a Scholar-in-Residence, during the week and on Shabbat. If you would like some “in person” sessions with me, please contact me at emalamet@gmail.com or check me out at the Jewish Speakers Bureau.

Stay safe and take good care of yourselves.

Further Reading

Shane Burley, “Jewish Activists Mobilizing Against War Are Finding a New Community.” New Lines Magazine. January 15, 2024.

Peter Berger, A Far Glory, 1992.

Yoram Hazony, The Dawn, 1995.

So happy you’re writing on this subject. This has been something I struggle to navigate.